A monumental literary achievement in a year for National Parks

By Glenn Nelson

Tuan (Q.T.) Luong has been down many pothole-filled roads during his 20-year quest to photograph every national park in the country. He once nearly lost his vehicle to the deep ruts of an unpaved thoroughfare to Sheep Mountain Table at Badlands National Park in South Dakota. He was better prepared for a drive up Mount Washington in a remote corner of Nevada’s Great Basin National Park; for that, he borrowed his wife’s SUV. But while the vehicle provided peace of mind on switchbacks so steep he had to take them with three-point turns, it didn’t help when, in those pre-GPS days, he took a wrong turn and missed sunset — the landscape photographer’s ultimate nightmare. And when Luong finally did reach the summit in the dark, one of his tires went flat.

During his quest, Luong survived a mosquito attack at Biscayne National Park in Florida, snapped photos with a cholla cactus barbed into his backside at Joshua Tree National Park in California, and narrowly avoided being stranded by flash floods at Big Bend National Park in Texas.

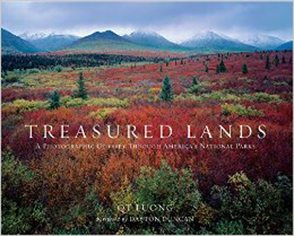

The perseverance and suffering paid off: Luong’s Treasured Lands — at 456 pages and nearly 7 1/2 pounds, with more than 500 photographs, 60 maps and 130,000 words — is the single-most monumental literary achievement during a year that brimmed with words and pictures dedicated to the centennial of the National Park Service.

Calling it a coffee-table book, or even a picture book, would be dramatically shortchanging Treasured Lands. To be sure, it is a visual feast. Luong’s compositions, many taken with a 5×7 large-format camera, are mesmerizing: Witness the full-page picture of a hiker looking down into Yosemite Valley from Taft Point at sunset. But it’s much more than that, because of its geographic completeness and the attention to detail that only someone who has lived and breathed the parks for a long time could provide.

Born in France to Vietnamese parents, Luong gave up a career as a computer scientist to become the first person, by 2002, to photograph all U.S. national parks with a large-format camera — something even the late, great Ansel Adams could not claim. Luong, now 52, taught himself how to operate that camera, which can hike his backpack weight to as much as 70 pounds. He also figured out how to undertake the project without financial backing, so he could do things exactly the way he wanted. That included going back to the same parks repeatedly to find the extraordinary image.

Juvenile owls in Pine Creek Canyon, Zion National Park, Utah (photo by QT Luong).

Juvenile owls in Pine Creek Canyon, Zion National Park, Utah (photo by QT Luong). Dawn at Cholla Cactus Garden, Joshua Tree National Park, California (photo by QT Luong).

Dawn at Cholla Cactus Garden, Joshua Tree National Park, California (photo by QT Luong). Tunnel View, Yosemite National Park, California (photo by QT Luong).

Tunnel View, Yosemite National Park, California (photo by QT Luong). Pronghorn at Rankin Ridge, Wind Cave National Park, South Dakota (photo by QT Luong).

Pronghorn at Rankin Ridge, Wind Cave National Park, South Dakota (photo by QT Luong). Grand Prismatic Spring, Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming (photo by QT Luong).

Grand Prismatic Spring, Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming (photo by QT Luong). Tetons from Cascade Creek, Grand Teton National Park, Wyoming (photo by QT Luong).

Tetons from Cascade Creek, Grand Teton National Park, Wyoming (photo by QT Luong). Nighttime at Canonball Concretions, Theodore Roosevelt National Park, North Dakota (photo by QT Luong).

Nighttime at Canonball Concretions, Theodore Roosevelt National Park, North Dakota (photo by QT Luong). Temple of the Moon and Temple of the Sun, Cathedral Valley, Capitol Reef National Park, Utah (photo by QT Luong).

Temple of the Moon and Temple of the Sun, Cathedral Valley, Capitol Reef National Park, Utah (photo by QT Luong). Doll House Towers and Milky Way, Maze District, Canyonlands National Park, Utah (photo by QT Luong).

Doll House Towers and Milky Way, Maze District, Canyonlands National Park, Utah (photo by QT Luong). Lightning thunderstorm, Big Bend National Park, Texas (photo by QT Luong).

Lightning thunderstorm, Big Bend National Park, Texas (photo by QT Luong). Snake Range and Wheeler Park from Mount Washington, Great Basin National Park, Nevada (photo by QT Luong).

Snake Range and Wheeler Park from Mount Washington, Great Basin National Park, Nevada (photo by QT Luong).

Luong made sure, for example, that he photographed at each of the five islands that make up Channel Islands National Park in California, all three islands that make up National Park of American Samoa, the three main keys of Dry Tortugas National Park in Florida, all five districts of Canyonlands National Park in Utah, and all three units of Theodore Roosevelt National Park, including Elkhorn Ranch, in North Dakota. He shunned the obvious, waiting for the right moment or returning for it. He stepped into Paurotis Pond in Everglades National Park with an alligator, to better capture the side lighting on the Spanish moss-covered trees at sunset. He hiked, climbed, swam and rappelled into Pine Creek Canyon in Zion National Park, to retrieve an unexpected image of a pair of juvenile owls sitting on a rock in a slot canyon.

“I’m not sure I’ve been particularly relentless,” says Luong, who lives in San Jose with his wife, two children and dog. “If someone’s hobby is, let’s say, running, they will train several times each week. … I suppose I keep returning (to the parks) because I don’t think it is a finished job. Besides new places, I like to see different seasons and weather, and I like the combination of the new and the familiar.”

Luong says his photographic park forays number more than 300, a figure he terms a “conservative estimate.” He has visited all but American Samoa and Kobuk Valley, Alaska, at least twice, and 46 parks at least three times. He’s been to Death Valley 11 times, second only to Yosemite, which he’s visited so many times, he’s lost count.

Yosemite literally is a whole other book for Luong — he published Spectacular Yosemite with Universe in 2011, and his image of Yosemite Valley graces the cover of Ken Burns’ documentary, The National Parks: America’s Best Idea. (Luong himself appears in the fourth episode.) Looking for what he thought would be short-term studies in the U.S., he chose the University of California, Berkeley, because of its proximity to the climbing mecca. And he never left.

However, Luong found the Sierra Nevada less impressive than the glaciated peaks of the Alps, where he mountaineered and guided during college. So, in 1993, he tackled the 20,308-foot summit of Denali, then still called Mount McKinley. There, he acquired what he considers the most difficult shot that appears in Treasured Lands. After a bush-plane ride and two weeks of solo climbing, the film in his pro Nikon snapped during rewinding because of the extreme cold. He couldn’t risk inserting new film because opening the camera would likely have clouded the shots he’d already taken. So Luong made the shot with a point-and-shoot.

Sunrise at Tutuila shoreline, National Park of American Samoa (photo by QT Luong).

Sunrise at Tutuila shoreline, National Park of American Samoa (photo by QT Luong). John Hopkins Inlet, Glacier Bay National Park, Alaska (photo by QT Luong).

John Hopkins Inlet, Glacier Bay National Park, Alaska (photo by QT Luong). Mangroves at Boca Chita Key, Biscayne National Park, Florida (photo by QT Luong).

Mangroves at Boca Chita Key, Biscayne National Park, Florida (photo by QT Luong). Paroutis Pond was shared with an alligator to capture sunset at Everglades National Park, Florida (photo by QT Luong).

Paroutis Pond was shared with an alligator to capture sunset at Everglades National Park, Florida (photo by QT Luong). Fort Jefferson Moat, Dry Tortugas National Park (photo by QT Luong).

Fort Jefferson Moat, Dry Tortugas National Park (photo by QT Luong). Wonder Lake, Denali National Park, Alaska (photo by QT Luong).

Wonder Lake, Denali National Park, Alaska (photo by QT Luong).

Inspiration Point, Anacapa Island, Channel Islands National Park, California (photo by QT Luong).

Inspiration Point, Anacapa Island, Channel Islands National Park, California (photo by QT Luong).

Within weeks, Luong visited the highest and lowest points in the National Park Service. His Death Valley days contrasted dramatically to those at Denali, and he marveled at the range of biodiversity. “There were a lot of new experiences for me in Death Valley, but I was impressed by how easy it was to access the park, as opposed to the mountain summits,” Luong says, “and I realized that this was a benefit of the National Park Service infrastructure.”

Ease of access seldom seems the motivation behind the choice of the scenes that Luong records in Treasured Lands. In fact, the degree of difficulty is so pervasive as to seem deliberate. But he says that isn’t the case.

Then call him undaunted and uniquely inspired. Tuan Luong, after all, has a Chihuahua named Peanut and says, “Despite widespread skepticism, I’ve run half-marathon distances with him several times.”

Luong’s work stands out on the crowded shelves of national park tomes because of the generosity not just of his vision but of his accumulated wisdom. Dayton Duncan, who wrote and co-produced Burns’ landmark documentary, pens the forward for Treasured Lands, but the remainder of the book’s words are from Luong. Each park gets its own chapter, as well as an introduction summarizing its most appealing characteristics and best seasons.

QT Luong, crossing Root Glacier with a typically overloaded backpack in Wrangell-St. Elias National Park, Alaska (photo courtesy of QT Luong).

QT Luong, crossing Root Glacier with a typically overloaded backpack in Wrangell-St. Elias National Park, Alaska (photo courtesy of QT Luong). QT Luong with his 5x7 large-format camera at Polychrome Pass in Denali National Park, Alaska (photo courtesy of QT Luong).

QT Luong with his 5x7 large-format camera at Polychrome Pass in Denali National Park, Alaska (photo courtesy of QT Luong). QT Luong, camping by Lampflug Glacier, Glacier Bay National Park, Alaska (photo courtesy QT Luong).

QT Luong, camping by Lampflug Glacier, Glacier Bay National Park, Alaska (photo courtesy QT Luong). QT Luong, photographing the Great Kobuk Sand Dunes in Kobuk Valley National Park, Alaska (photo by his wife, Lanchi Vo).

QT Luong, photographing the Great Kobuk Sand Dunes in Kobuk Valley National Park, Alaska (photo by his wife, Lanchi Vo).

For an avid photographer and national park fanboy like myself, the real treasure trove is buried in Luong’s descriptions of the images, which are plotted on a map and accompanied by precise directions, details and anecdotes. Where else, for example, will you learn that bison, pronghorn and prairie dogs are more easily observed in South Dakota’s Wind Cave National Park than in its more highly touted sister park, Badlands? Or read an admission that he and a friend were so overcome with awe at John Hopkins Inlet in Glacier Bay National Park that they almost failed to notice an oncoming brown bear? Or cop the honesty of a gem like, “Despite its name, I didn’t find Inspiration Point too inspiring,” about a perch above Jenny Lake in Grand Teton National Park? (Now that I’ve been there, I agree; it doesn’t live up to the hype.)

Luong’s generosity extends to the practical: He offers purchasers of Treasured Lands a more portable and easily readable electronic version of his photos and commentary. At TreasuredLandsBook.com, he even offers links to merchants selling his book at discounted prices.

Best of all, Luong is willing to share turn-by-turn, step-by-step directions to the exact locations of his images, as well as commentary about the best time of day, or season of the year, during which to photograph them. Most photographers treat such data like state secrets, merely sharing camera and exposure data, which usually are useless because conditions and lighting are ever-fluid variables.

“More often that’s a way to prevent others from getting a similar shot,” Luong acknowledges. “This stems from insecurity and runs opposite to what I am trying to do with my photography, (which is to) inspire people to want to see with their own eyes the places I saw. I also recognize that I’ve benefited from the collective knowledge of many landscape photographers, and I am trying to pay it forward.”

We, the fans and stewards of a marvelous system of history and protected landscapes, are the beneficiaries.

ALSO: Sense of Yosemite, offers an intimate look at a single, iconic national park.